A Verdi puzzle

Giuseppe Verdi was born close to the “bel canto triumvirate” Rossini-Donizetti-Bellini, but lived and worked so much longer that we see his as a different era. This affects the way we think about his music and its performance - there is a natural tendency to hear Nabucco and Ernani more as “predecessors of Aida” (composed nearly three decades later) than as “companions of Don Pasquale” (composed a little after Nabucco). But when we look at Verdi’s earlier works, we see forms and vocal gestures inherited directly from the “triumvirate,” and so the question naturally comes up: were they ornamented by their interpreters in a similar way?

It’s a big topic with many facets, and one of them is illustrated by a clue from the unlikely source of Lillian Nordica’s records. In her very first session she made two takes of “Tacea la notte” from Il trovatore, and its opening lines provide a surprise. Here they are (from Take One; the second is slightly different), with a score to follow:

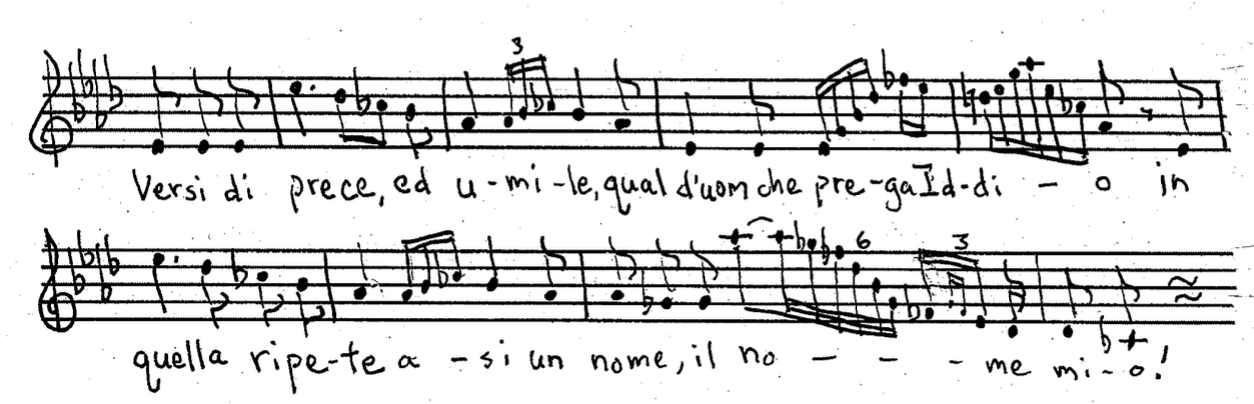

It’s startling to hear these rangy variants at the very beginning of the piece, where Leonora is merely setting the scene for the story she is starting to tell. But this is misleading: In order to fit the aria and its cabaletta on a single side, Nordica performed only one stanza of each. If we assume that the ornaments would have been reserved, in a complete rendition, for the second strophe, the first of them would fall on the lines about the Troubador’s verses rising “like those of a man beseeching God,” and the second on the burst of enthusiasm when Leonora hears her own name invoked in those prayers. Here is how they would look if transcribed there instead of where Nordica recorded them:

Early records of Verdi are full of ornaments, but most of them are a matter of an added turn here, some extra grace notes there, a passing-tone or two, an amplified cadenza. These are full-scale “variations” of the dimensions we associate with a cabaletta repeat in Rossini or a Baroque aria da capo. Was Nordica doing something eccentric, or was she carrying on a traditional process that survived longer than people think?

Several record-collector articles and liner notes associate her ornaments with Therese Tietjens (1831-1877), who had at least some connection to the composer: she was his soloist in the Inno delle nazioni when the cantata was first performed in 1862. I have never been able to find any account from Nordica’s lifetime that asserts this directly, but readers of Yankee Diva will easily see how the connection could be made.

We know from the biography that young Nordica heard Tietjens sing Il trovatore in Boston in 1875, and that Tietjens in turn heard her sing the aria: she had granted the 17-year-old soprano an audition, and requested “Tacea la notte” after hearing Lucia’s Mad Scene. Moreover, Nordica proceeded the next summer to a course of repertory study with Apollonia Bertucca Maretzek, wife of the impresario who brought Tietjens to Boston, who had been a prominent soprano in youth and was now the harpist of her husband’s orchestra. That is not exactly evidence that the variations came from Tietjens, but it is certainly a more-than-plausible chance for Nordica to have picked them up if they did.

Many years ago, curious whether the singer’s own scores might contain further clues about this, I drove on icy back roads in the dead of winter to the Nordica Homestead in Farmington, which is maintained as a rustic museum. At that time it was still heated by wood-burning stoves and inhabited by descendants of the diva’s employees. Dozens of costumes were mounted on mannequins, and hundreds of scores (including orchestra parts for concert tours) were packed in uncatalogued boxes in the library. They proved fascinating in ways large and small. Among the small: it seems that practically every season Nordica purchased a new copy of Rossini’s Stabat Mater (Schirmer edition, whose price rose from fifty cents to seventy-five cents over the years she did this), annotated it with her breath marks, and put it on the shelf when she was next at home. There were twelve of those.

And she did write her ornaments into her music - good! Some singers don’t! (I had a hunch she might have been among those who did, because in her “Hints to Singers” she lays great stress on the importance of musicianship and sight-reading.) So I found fascinating details about how Semiramide was sung in the last years before it disappeared, and many interesting bits for arias Nordica used in concerts. Then at last Trovatore came into view: chock full of embellishments and interpretation marks, some of them intriguingly old-fashioned. Three different cadenzas for “D’amor sull’ali rosee.” But for the entrance aria - not a scratch! Virgin pages.

Lack of information is sometimes informative: in this case, it suggests that when Nordica first prepared the role of Leonora (Berlin, 1888), she had already settled her interpretation of the aria, and didn’t need to jot things down the way she did on practically every other page. That supports the notion she might have taken some hints from Tietjens.

On the other hand, maybe these decorations (or something like them) were “going around” even earlier, and could have reached Nordica by other routes. Heinrich Panofka, writing in 1871 about one of Verdi’s great faves Erminia Frezzolini (1818-1884, the first Giselda and Giovanna d’Arco), made a point of describing her interpretation of this very aria: “in the reprise, she inserted two fioriture of such delicate taste, and so distinctly touching, that if Verdi heard them he must have felt vivid regret at not having created them himself.” Frezzolini too had sung Leonora in Boston - too early for Nordica to hear, but not for her teachers.

So in the end - barring further discoveries - this is not one of the cases where we can trace a fascinating ornament to a precise point in the historical record. But without Nordica’s approach to the gramophone, however mixed its success, we wouldn’t even have the question to ask, and we would be missing an important example of the way the opera world understood Verdian style.

![Image 2 - Henry T. [Harry] Burleigh - Detroit Public Library.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/596bb4e703596e837b624445/1591713684327-N7HW488JSZ7EN8T5AJSR/Image+2+-+Henry+T.+%5BHarry%5D+Burleigh+-+Detroit+Public+Library.jpeg)